Hi Norman,

I left Gothenburg many years ago for Tasmania to do a PhD with you and Kate. It’s one of those decisions I have never regretted. It felt more like joining a family than a research lab. You and Kate has kept the laboratory small in order to look after the lab and everyone working there properly. I think this is a great concept. I had actually met you previously during some of my undergraduate courses when I was an exchange student and it really got me interested in neuroscience. It was a while ago but a lot of what you taught me still feels very relevant and still often helps me in my decisions. You have been a pillar stone in the blood-brain barrier field and I owe a lot of my research career to this. We are all evidence of your success and great mentoring.

So I wish you all the best for future and hope we can still manage to do some projects together.

Joakim

From Laurence Smaje

Dear Norman

It’s a pleasure to write ‘a little something’ about our time(s) together, as Kate put it in her email.

We both did PhDs in the Physiology Department at UCL, me after I’d finished medical studies in 1962 and you, I seem to recall, between the intercalated BSc and the clinical course. However, we both ended up a few years later as Lecturers in the department, though working in different fields. Even there, our interests crossed later after I returned from a sabbatical in the USA after which I switched to working on the physical and exchange properties of single capillaries.

Our closest working relations, however, were with teaching and examining medical students. When working together examining the unfortunate students who were slightly above or slightly below the pass mark in their written examinations, I remember that you thought I asked really difficult questions and I thought the same about you. Maybe it was because we didn’t know the answers to the questions the other was asking!

Over the years we kept in touch, you at Southampton and then Hobart and Melbourne and me at Charing Cross & Westminster and then the Wellcome Trust. On one occasion you invited Deirdre and me to Hobart as your house there was not used very frequently after your children had graduated. A year or two later, we took you up on this kind offer and we had a wonderful holiday in Melbourne and Hobart where you and Kate were the most thoughtful and delightful of hosts.

So Norman, congratulations on your celebrations and may there be many more to come.

Laurence

From Lester R. Drewes

“Stickler and Encouragement” By Lester R. Drewes

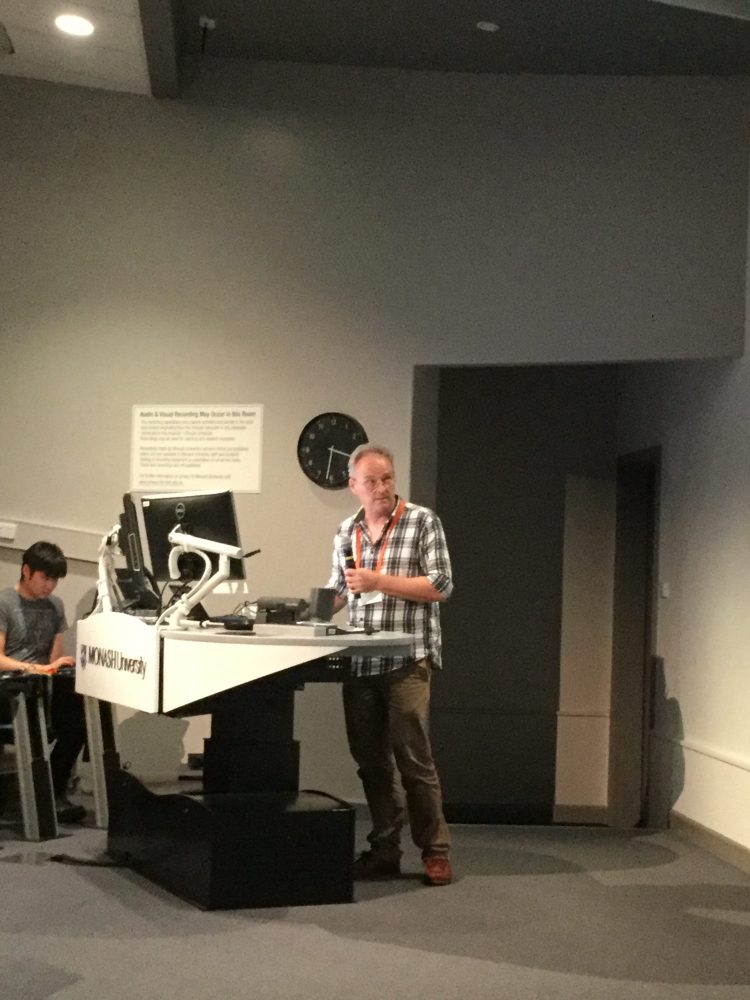

The musical sounds of a calliope and drums drifted into the street from the nearby Tivoli Gardens. That was the prelude to my first recollection of Norman Saunders at the Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters, August 23, 1998 in Copenhagen. (See photo.) This was the beginning of many encounters with a person with great wit, deep knowledge of his trade, impatience for ignorance, and generous with encouragement.

Norman is an expert in the field of the choroid plexus, CSF dynamics, and development and function of the blood-CSF barrier. Using traditional methods is quite acceptable to Norman, but when a proven improvement comes along, the old should be discarded. He was a stickler for scolding many brain barrier novices who claimed to measure “opening of the blood-brain barrier with Evan’s blue dye staining” when a fluorescent dextran would do much better. Personally, however, I will always remember the advice and counsel that he generously provided during the fledging days of the International Brain Barrier Society (IBBS). Once on a Long Island Railway train on the way to Cold Spring Harbor, we had a half hour dialog concerning IBBS bottlenecks and political travails. His ability to listen, to analyze, to separate the chaff and immediately propose solutions was for me like an ethereal visit with Confucius. This was combined with absolutely staunch encouragement to continue on a goal-oriented path. I am eternally grateful for his kindness, friendship and guidance in moving the field and our community forward.

Pictured left to right: Malcom Segal, Lester Drewes, Lorris Betz, Richard Keep, Ron Blasberg, Jeff Rosenstein, Rolf Gruetter, Joe Fenstermacher, Norman Saunders, David Begley, Quentin Smith (Copenhagen, 1998)

From Lyn Hinds

I first met Norman and Kate in the early 1980’s when they came to work with Hugh Tyndale-Biscoe and myself at CSIRO Wildlife and Rangelands Research, Canberra, Australia, on the development of the brain and blood brain barrier of the pouch young of the tammar wallaby, Macropus eugenii. This proved a very successful and productive collaboration with Norman and Kate visiting several times over the next few years - perhaps our times together in some way influenced their decision to come to Australia in the late 1990’s! I have extremely fond memories of visiting them for 3 months at the University of Southampton in 1989 to undertake a reproductive hormone study of induced ovulation in the South American opossum, Monodelphis domestica. Norman and Kate, Krystyna and Peter were great hosts and collaborators!

In the last few years, since their move from University of Tasmania to University of Melbourne, we have commenced another fruitful collaboration, this time using the tammar wallaby as a model bipedal species for studies of spinal cord injury. We have achieved some interesting and valuable results (though no-one wants to fund it!).

Norman sets high scientific standards for himself and those around him – and loves a good wine, juicy steak and a chat about politics! May there be many more years to enjoy the scientific and other discussions!

Lyn Hinds,

CSIRO Health and Biosecurity

Canberra

From Dom and Nadine Hodgson

Dear Norman,

Our lives have been enriched by friendship with you Kat, Peter and Krystyna over the last 20+ years!

Very best wishes from Dom, Nadine, Isla and Ynes

From Zoltan Molnar

I have known Norman from the time I landed at Oxford in 1988. I helped Kate and Norman to get some CSF in the Blakemore Lab and we started talking about brain development and blood brain barrier. It was the beginning of a very fruitful collaborative interactions. We worked on various areas and in different species and we met in Oxford, SFN meetings in the US, Melbourne, Hobart, Copenhagen, but my visit in 2015 stands out when I crossed Tasmania with Norman and Kate. It is still one of my most memorable road trips. The majority of the photos were taken on this occasion.

I hope to continue to collaborate with Kate and Norman for many many years to come.

Yours ever,

Zoltan

From Victor Iwanov

It has been said that first impressions can often leave an indelible stain upon your psyche and my early interactions with Norman certainly support this observation! Allow me to recount, and please note that my recollections may be not completely accurate....

It was at my Club, during a science outreach session for dipsomaniacs, where Norman was the invited speaker. He delivered an erudite and scientifically comprehensive discourse of his neurophysiological adventures in the UK and the antipodes, and whilst I did not comprehend all the graphs and pie charts, at his conclusion I nevertheless felt intellectually enriched by his passion for science, or maybe I was just glad the canapés had arrived? Anyway, after the talk, Norman came over to chat to me, and in my excitement, I spilled my drink over his shoes. Looking up from his feet, Norman noticed that I had the latest copy of ‘An Epicureans’s Guide to Opossums’ in my pocket and as he looked at me, he tersely remarked “Did you know that the opossum spinal cord has astounding regenerative capabilities following blunt force trauma?” I thought that, on account of the spilled pint, he was going to give me some blunt force trauma, but he seemed to be in a forgiving mood. I said “No I didn’t – regionalerative ... fascinating!” Next thing I knew, Norman slapped me over the head with a book he had just published, thrust it into my hand and remarked that it may prove more interesting than a compendium of marsupial recipes! He said they were too chewy anyway... I glanced at the lurid cover of Norman’s pamphlet and saw that whilst it may indeed prove interesting, I couldn’t help but wonder that if I stuffed it into his shoes, would it absorb the beer from his socks? The slim tome was as much an eye opener as it was an eye closer because after 12 or so pages in, I fell asleep and dreamt of endemic south American native animals. The physics of small molecule diffusion processes across selectively permeable membranes always does that to me! Some time later, I was woken by the cleaner. Norman had gone, I had a second bump on my forehead (apparently Norman was not as forgiving as I thought...) and I found a pair of damp socks in my pocket.

Norman and I renewed our relationship when he came to Melbourne to spread his brand of intellectual pedantry … or is that physiological pedagogy? He had an enthusiastic research group and had been awarded an enormous grant to study the effect of car crashes on spinal cord integrity and wound healing in some poor defenceless species. As an ancillary project, once the cords healed, he would then teach the critters to sail instead! (or something like that anyway...). I was going to help him administer this pot of gold! We met in the corridors of the Medical Faculty, and once again he must have been in a forgiving mood as I got the feeling that he was thinking that before him was an administrator he could work with – probably intellectually handicapped to be sure, but as long as the forms were filled in neatly he’d be satisfied. At the the very worst, he could teach me to sail as an honourary member of Sailability!

He had an interesting relationship with University administrators. He told me that back on the planet where he came from, they made him ‘mad as hell’ and ‘he wasn’t going to take them any more!’ I got that terse look again: “Did I understand?” I did once hear a rumour that the reason Norman was transported to Tasmania was because after a fracas with some HoD about an incomplete travel diary reconciliation, there were a number of Central Services apparatchiks hospitalised with head and neck injuries! Needless to say, Norman and I got on like ‘a house on fire’ as long as I did what I was told and did not look too closely at the finer details of the spreadsheets. I also returned his socks - darned, cleaned & ironed!

These days, whilst our paths cross mainly when he perambulates Royal Parade, Norman leads a more relaxed and a more easy-rider lifestyle!

Despite my tenuous grasp of the facts and my tinted view of history, and even though he was not forthcoming with any good opossum recipes, along with my amphetamine intake, Norman has had a positive effect on my psyche (you can hardly notice the stain) and I appreciated his considered and experienced input when I needed advice (or is that instruction?) about navigating the vagaries of tertiary education management. Norman, I salute you, and I wish you all the best as you take time to reflect on a satisfying and productive professional history, and now enjoy a future bereft of superfluous administrative rigmarole!

From Phil Waite

Dear Norman,

This is a story of intersecting lives for over 50 years, driven initially by science but later via medical education, and family friendships, crisscrossing the globe from England to NZ and Australia.

It started when I joined UCL as a Physiology student in the early 60’s and Norman was a demonstrator for our practical classes. We students held teachers in awe in those days (maybe less so now!) so interactions were strictly within class. Even as a PhD student, my research was electrophysiological and Norman’s was biochemical so communications were limited.

Our paths crossed again when I decided, at 38, that I wanted to study Medicine. My own Faculty in Otago, NZ, rejected my application (ostensibly because of age) and I applied to UCL. Unknown to me, Norman was Sub-Dean and head of the medical selection panel and I was invited for an interview. A big “thank you” to Norman for having faith in me and saying “yes”. This was a critical factor in persuading Otago to change its mind and accept me. An amusing aside is that I was admitted into 3rd year, joining students that I had taught and examined in their 2nd year.

In 1986, Norman, Kate and their young children were in Auckland on a sabbatical, while I was at Auckland Hospital, doing my ‘houseman’ year, also with my husband, Colin, and our two young sons. We have fond memories of shared family picnics with Kate’s famous cooking. While Norman and I were at work, Kate and Colin enjoyed taking all 4 kids swimming. By this stage Norman was Head of Physiology in Southampton and, post- medicine, I was keen to return to academe. A position at Southampton was seriously considered but lost out to UNSW, Sydney, mainly for family reasons.

Interactions really hotted up when Norman became Head of Physiology in Hobart, Tasmania, and I was based at UNSW. By then we had both, quite independently, developed an interest in spinal cord injury. Moreover, we were both using marsupial models for the unique early access they provided to the developing nervous system. This led to plenty of shared scientific interests, as well as those in medical education, and our developing young families. Discussions were always accompanied by great food and wine; Norman and Kate’s hospitality is legendary and has been much appreciated over the years.

Comments from two close friends and fellow scientists, Mark Rowe and Hendrik Van der Loos, are missing from these acknowledgements. Their sudden, untimely and tragic deaths shocked us all and robbed them of the chance to contribute here. They are much missed but not forgotten.

Thank you Norman, for all your friendship and support over half a century. Happy Birthday and please find time to enjoy your renewed health and your new grandson!

Photo taken by Geoff Raisman, at an ISRT meeting in Switzerland

From Udo Schumacher

In a certain way I am the odd one out in this collection as I am not a neuroscientist. I met Norman and Kate for the first time shortly after my arrival at Southampton University in fall 1990. They were the first ones to invite me to their home and as he had also recently been appointed to the chair of physiology & pharmacology , we had a lot of challenges (in those days called problems) in common with the university administration, which however did not deter us to do something, namely research. Norman and Kate were and are very hospitable and entertained a wide range of scientific friends in their house to whom I was priviliged to be introduced, namely John Nicholls, Kjeld Mollgard and William J. Krause. As the result of these discussions joint papers with Kjeld and Bill were published. I even had some input into neuroscience as a joint paper on my pet subject, carbohydrate histochemistry and glycobiology was published with Norman and Kate on the changes of glycosylation in the developing brain of marsupials.

My contact to Norman and Kate continued with their departure to Hobarth. He invited me to be external examiner in anatomy where I had the opportunity to stay in their marvellous beachside home and to meet even more interesting people like Peter Lisowski. When Norman and Kate moved to Melbourne, we still kept in touch and I applied for the chair pathology in Melbourne. Unfortunately that appointment did not come to fruition and so I remained in Hamburg.

I owe Norman a lot, not only his many enlightening and insightful comments on medicine, the somtimes unhelpful university administration (his lifelong battleground), and neuroscience. He really opened up my mind for neuroscience and hence that time I am looking for connections between neuroscience and cancer. The possible neuronal nature of cancer stem cells has become next to glycobiology one of my pet subjects. Without Normans help this would not have happened. What more can you expect from a scientific friend?

From Sam Richardson

To be sung to the tune of “I am the very model of a modern major-general” from The Pirates of Penzance, buy Gilbert and Sullivan.

He is the very model of a modern major pro-fess-or,

He’s information animal, barriers and spinal cord,

He knows the kings of CNS and can quote the fights historical,

From Stern and co to Liddelow in order categorical.

He’s very well acquainted with matters developmentally,

And understands conundrums that confound poor students hopelessly,

About cerebrospinal fluid he’s teeming with a lot o’ news,

With many cheerful facts about the bureaucrats he loves to abuse!

He’s very good at barriers and CNS border control,

I’m sure that Donald Trump wants Norman for his barrier patrol.

In short in matters animal, barriers and spinal cord,

He is the very model of a modern major pro-fess-or.

In fact when he knows exactly when the blood-brain barrier is developmentally made,

When he can tell at sight a scalpel from a razor blade,

When such events as taking me on sailing yachts I’m wary at,

And when he knows that ropes are sheets and ties a convincing lariat,

When he has learnt what progress has been made in modern seafaring,

When he knows more of tacking and of jibing when the wind is in,

In short when he’s a smattering of elemental strategy,

You’ll say a better pro-fess-or has never behaved more valiantly.

For scientific knowledge he is plucky and invigorating,

His breadth and depth of knowledge are nothing but intimidating,

But still in matters animal, barriers and spinal cord,

He is the very model of a modern major pro-fess-or.

With apologies to W.S. Gilbert and A.S. Sullivan.

From Gary Greenberg

Just to let you know how long I have known Norman Saunders, I have attached a photo of what I looked liked when I met him as a PhD student at University College London in 1977. I had been hired by the director of the film Superman to produce special effects reminiscent of the surface of the Planet Krypton. The solution was Human pancreatic cancer cells in vitro using DIC optics so that the nuclei of the cells looked like craters on the planet Krypton.

This was just about the same time that Norman met Kate, a match that has flourished all these years both professionally and personally, and produced two wonderful children, Peter and Krystyna, who are no longer children! This was when Norman asked me to work with him on filming the choriod plexus cells he was studying. I was fascinated by the behavior of these amazing little cells.

Norman has been tirelessly investigating spinal cord injuries ever since. After Superman Chris Reeves broke his neck, Norman helped to commandeer his support for spinal cord injury research. Norman has been a world leader in developmental neuroscience and neurotrauma research. He has mentored a number of students who have gone on to create world-class careers in science.

Norman and I have had the pleasure to share two wonderful sports together, sailing and skiing. After receiving my degree in Developmental Biology, I moved back to Los Angeles to continue my academic career. Norman and Kate visited on many occasions, usually on their way to or from various international neuroscience meetings. And, like-wise, I had the great gratification of visiting Norman's lab in both Tasmania and Melbourne on numerous occasions.

Looking back at this photo when Norman and I first met, it's amazing what happens to a person after looking through microscopes for 40 years. The good news is, Norman and I are still around, enjoying each other's friendship. Congratulations Norman on a life-time of great work spent furthering our knowledge of Neurobiology. It has always been both a pleasure and an honor to work with you. All the best, with aloha from your friend Gary.

From Doug Brown

Norman is a very practical as well as experimental scientist. His viewpoint reaches beyond academic interests to broader applications that can lead to improvements in people’s lives. He has made a very large contribution to the problems of regeneration and repair of the spinal cord in his laboratory work with the South American opossum. This work has substantially expanded our knowledge of the complexity of the problems of healing the damaged spinal cord and restoring functional pathways.

He has spent time with people with spinal cord injury to understand the problems they face in their daily activities. This had led him be actively engaged in innovative approaches to improve their lives. An example is his involvement in the development of a sailing simulator that enables anyone, including highly disabled people such as those with quadriplegia, to learn to sail an access dinghy and then transfer their skills to solo sailing on water. Being able to sail and compete on equal terms alongside those without disability can boost self confidence and encourage engagement in the general community. He secured funding and the co operation of other centres in different countries to undertake a trial to determine the effectiveness of sailing, using the simulator as a training tool, to enhance the quality of life for the spinal cord injured.

He has a very strong ethical sense and applies it to his own work and to the assessment of that of others. His analytical mind and intellectual rigour have enabled him to evaluate problems, research and publications so that he can assist researchers in their endeavours as well as formulate new approaches to solving problems. He applies these principles to mentoring young researchers, ensuring that the next generation will continue the tradition of research excellence that he himself embodies. As a mentor, he has had a huge impact on scientific research internationally. In these days of pressure to publish and limited funding, his personal integrity stands out in academic research.

I have been privileged to have worked with him helping those with spinal cord injury, and of being a friend.

Associate Professor Doug Brown

Executive Director, Spinal Research Institute

Formerly Director, Victorian Spinal Cord Service

From Phil Vardy

I first met Norman Saunders through a common interest in sailing. Norman had developed a sailing simulator that could be adapted to the needs of sailors with disabilities. I was involved in empowering such people through sailing.

In 1997, I was invited to be part of the organising committee of a scientific conference to be held in conjunction with the 2000 Sydney Paralympic Games. It soon became apparent that the committee would benefit enormously by the involvement of Norman Saunders, a man whose background, like mine, straddled both science and sport. I therefore suggested that the chairman invite Norman to join us.

As a committee, we faced a daunting task. We had to work with both a governing body that often appeared to favour style over substance, and a conference organising company that often appeared to put profit before performance. Nevertheless, a superb conference resulted.

During planning sessions, I drew a series of cartoons illustrating some of our difficulties. The cartoons were never meant to be permanent. Quite the opposite: most were scribbled in haste on the backs of agendas. Nevertheless, the chairman collected the cartoons. He later assembled them into binders and distributed them to members as souvenirs.

Several cartoons featured balloons, a reference to the chairman, Greg Gass. Others feature Glen Davis, a colourful member of the committee. No cartoon of Norman survives, but I trust that he will remember our work as did the chairman: ‘memorable, fun and highly enjoyable.’

Phil Vardy

From John Foreman

Dear Norman,

I send my best wishes for your birthday celebrations.

I have known you now for nigh on 50 years and I value our friendship over all those years.

I am eternally grateful to you for two things that you have given me. First, you nominated me as your successor as Faculty Tutor at UCL. In that role, I followed, I hope, in your footsteps by encouraging the admission to medicine of the best students, irrespective of their social status or schooling. You were light-years ahead of current thinking on this issue. That opportunity was to set the scene for my career at UCL. Second, you gave me the opportunity to teach the medical students at UTAS. This was one of the most rewarding experiences of my life. Why? It was a small medical school by current standards but one which took great care of its students. They responded with their enthusiasm for learning. What a wonderful bunch they were! I recall one day that I had to cancel an afternoon tutorial. Their response was to suggest I did the tutorial at 8am the following day. One of the students even picked me up from my accommodation and drove me to the tutorial!

Thank you to for bringing me to Tas. It is one of the most beautiful places on the planet and I am privileged to have spent so much time there. The hospitality that you and Kate afforded me on my visits was astounding.

Norman, you have always courted controversy. In my view, rightly so by irritating the ‘establishment’ who have lost sight of the real nature of what a university should be. I hope you will look back with pride in what you have achieved. You should!

With my warmest regards.

John Foreman

From Joan Abbott

Dear Norman

I first met you in 1970-71 when I was working as an SRC post-doctoral ‘Resettlement Fellow’ at University College London (UCL) in Hugh Davson’s lab, on my return from a post-doctoral year in USA. Hugh said the fellowship sounded like one designed for ex-inmates returning from the penal colonies. Hugh was an enormously influential figure and guru for us all, effectively the founder of UK studies on the barriers of the CNS, the BBB, B-CSF barrier and blood-eye barrier. You may recall that the Davson lab was on one side of a narrow corridor in the old Physiology building. On the other side was a tiny workshop where much of Hugh’s equipment was hand-made by the ingenious and highly-skilled Charlie Purvis, alongside a bigger lab where in vivo experiments could be conducted. You were at that time pioneering studies on the development of the mammalian choroid plexus, by examining CSF of exteriorised sheep foetuses, a demanding operation involving several large men including yourself and Malcolm Segal wrestling an enormous and not very enthusiastic sheep into position for anaesthesia and surgery. I am sure you were too preoccupied to even notice me, but I do remember the scene vividly.

As you know, in those days the scientific and social hub for UK BBB/CSF scientists was the Physiological Society, with monthly meetings rotating around UK universities. Presenting a 15min talk at meetings was a daunting baptism of fire for us new recruits, but we aspired to publish our work in J Physiology, as you did for many of your pioneering papers. After I moved to King’s College London in 1972 I admired your rapid rise through the ranks at UCL, until you moved to Southampton as Head of Department in 1986. It was clear you relished the chance to pursue your passion for sailing as well as science. I very much enjoyed visiting you and Kate during those years – you were enormously welcoming, wonderfully hospitable, you family dinner table a lively meeting place for an appreciative group of scientists and friends. Your move to Tasmania in 1992 seemed entirely in keeping – your love of adventure, the outdoors, the challenges, the home on the waterfront, and greater access to neonatal marsupials for developmental studies. You organised a memorable meeting at Freycinet Lodge in 2001 as a satellite to the Physiological Congress in Christchurch NZ: wonderful surroundings, delightful wine tasting and some excellent science.

I imagine your move to Melbourne in 2002 made it easier for you to continue your innovative and productive research collaborations in Australia and round the world; it was always a pleasure to see you and discuss. Your survey of BBB history at the CVB2014 meeting was a masterpiece – continuing your long tradition of correcting errors and myths. I suppose like us all you had some prejudices and blind spots – you seemed somewhat suspicious of electrical measurements such as TEER, preferring to rely on visible permeability tracers, including many your group introduced. You could sometimes appear crusty and critical; I remember you complaining at one Gordon conference that the BBB field seemed to be stuck in the past. But I think you were deliberately challenging us to adopt new ideas and technologies. Indeed, you have been one of the prime movers in keeping the field lively, and in training gifted young scientists to spread the word and establish groups of their own.

It has been a great pleasure to know you for more than four decades, and I do hope to be able to share in the celebration of your birthday, and your life and work, in Melbourne at CVB 2017.

With very best wishes,

Professor N. Joan Abbott.

From Michael Lane

Dear Norman,

It is with the most heartfelt gratitude that I write this note of thanks for all that you have done for me and my career. It is so great to hear of this special acknowledgment of your life-long commitment to science, and it is such an honor to have the opportunity to contribute to it.

I still recall fondly my first lectures with you in neuroscience, physiology and pharmacology at the University of Tasmania. I remember feeling so lucky as a student to have the chair of the department meet with me to talk about past and present research, and to sit with you at the microscope and look through sections of the developing opossum brain and spinal cord. Thank you for being so patient as I was learning. Hopefully I didn’t make too many mistakes along the way. I learned so much from you during my undergraduate studies, throughout my graduate research, and I still learn from your example to this day.

You are a remarkable scientist and an incredible person to whom I owe a great deal. You trained me for a career that I truly love and continue to be excited by every day. I would not be where I am today – pursuing my passion – if it were not for your mentoring, kindness, support and friendship. With all my heart, thank you Norman.

With warmest of wishes on this special day,

Michael Lane

From Joanna and Adam

To Norman:

It was October 1992 in Anaheim, CA when we met for the first time. This was slightly over a year after our arrival in the US, and our first big meeting on this continent. I was very nervous standing by the poster by myself when I saw a guy with the backpack heading toward me. He stopped in front of our poster and communicated with strong British accent: “my wife Kasia, who is Polish as you are, asked me to check on you”-and that was the beginning of our friendship that continues to these days.

We keep seeing each other at least once a year at various meetings either here in the US or in Europe. But we also visited Kate and Norman at their lovely house in Hobart. We had a great time together since they both are exemplary hosts. Although Kate has never visited us, their son Peter spent some time with us, and Norman also paid a visit to our house in Providence. We always had fun together whether it was when we dined out or when we were “crossing swords” in heated scientific discussions. We were simply taking pleasure in each other's company-enjoying good music or drinking good wine.

Adam and I are extremely happy that we could participate in this special symposium dedicated to Norman's long scientific career and also to celebrate his belated 80th birthday. It is even more exciting that this celebration is taking place in Melbourne that has been home to Kate and Norman for a long time.

Here is a toast to you Norman-to many more years of great research coming out of your laboratory and to friendship that has past the test of time.

With very best wishes,

Joanna and Adam

From John McDonald III

To Norman Saunders

What can I say about an icon- British to boot!!!

Dr Saunders as we know him is true icon in the field of neuroscience- really- lol

I first crossed paths with the good doctor when I wanted to use a very important model of CNS injury. Where the hind limb development occurs ex utero. Banana flavor was the key- it was then I knew I admired this scientist that I would later become close friends despite an 80 yr age difference!

I remember Kate his better half--(by a long shot). I remember New Orleans and tackling the hand Grenade manikin at neuroscience- and drinking a few also.

I remember a tumultuous ferry to Hobart eating Sydney Rock Oysters along the way- I remember the beauty of Hobart- not Norman- lol

What reconciles most with me is a true friend- concerned when needed, a true gift of life- though I still like Kate better!!!

I recall an incredible hospitality, which I am sure Kate is responsible

Did I mention Kate?

I love you my brother and I would not be a friend unless I admitted that your humility is Kate engendered- lol

Indefatigably yours,

Johnny

Best,

John McDonald III

From Joe Fenstermacher

Dear Norman:

As you correctly wrote in the booklet from the 2014 Symposium honoring my retirement, we first met at the 1976 meeting organized by Hugh Davson, Laszlo Bito, and me at the NIH. The title of the meeting was “The Ocular and Cerebrospinal Fluids” and the proceedings were published by Experimental Eye Research as a special issue. The title of your presentation was “Ontogeny of the Blood Brain Barrier,” and it was a scholarly work covering not only your own studies but also those reported by others over the years. The most striking part of your presentation was, however, the first slide (these were the days before PowerPoint), which I vividly remember. It showed several shepherds driving hundreds of sheep down a London street, possibly Oxford Street or the Strand. You said that these animals were on their way to your laboratory at University College London and that sheep offered a great model for studies of blood-brain brain development in foetuses (note the proper British spelling). Your presentation is well recorded in that issue of Experimental Eye Research (Volume 25, 1977. Supplement), and I urge one and all to read it.

My next interaction of note with you and with Kate was in your office at University College London late in the year 1977. I was on a sabbatical leave from the NIH studying with Hugh Davson and Mike Bradbury at Kings College London. Your office rivaled that of Cliff Patlak, stacked full of papers, journals, lab notebooks, and other repositories of data. In those cozy quarters, the two of you brought me up to date on your findings since the NIH meeting, and the conversation rolled on for hours, ending only when it was time for a trip to a local pub, a bit of beer, and more discussion.

We continued to see each other at various neuroscience meetings over the following years. Most notably, you, Kate, and I attended the first Gordon Research Conference on Barriers of the CNS, held at Tilton School, Tilton, New Hampshire in August of 1999. Thankfully, Joanna and Adam Chodobski, the organizers of this conference, brought you and me together once again. At this meeting, we not only discussed brain barriers but also engaged in various indoor and outdoor sports. With respect to the latter, one morning you observed me returning from my daily run of 4-5 miles and shook your head in disbelief at such madness. You then commented that you had given up running when you were a youth and had taken up a sensible sport, sailing, which you expected to be able to do for the rest of your life. True to that, you are still a sailor of small boats and have produced a sail boat simulator model for training others in that worthy art.

To continue with sailing, you have told me that it has been recommended by your several doctors to drop bicycling, which could lead to a nasty fall and broken bones, and to take up swimming to keep in shape prior to hip surgery. When I responded that I do a lot of swimming to keep physically fit and am building a swimming pool in my backyard in Seaville, NJ, you replied that an important part of sailing small boats is not to go swimming because it is a failure of sorts. As you added, this view of swimming has been acknowledged by such famous sailors of big boats as Denis Connor, a highly successful America’s cup skipper. So, Norman, I hope that sailing keeps you physically fit and that you smoothly “sail” through your upcoming hip surgery.

In 2001 you and Kate organized a Cerebrovascular Biology meeting at Freycinet, Tasmania, Australia. I was pleased to be invited and attended. Several of us including the Chodobski’s stayed at your home on Sandy Bay, Hobart, Tasmania, both before and after the meeting. There we enjoyed much conversation, camaraderie, and coffee. The latter was especially fine and was made with a French press. I raved about this coffee so much that Joanna got me a French press after we returned to the States. I think of you and the rest of the group every time I use the French press for making my morning coffee.

It was also at this meeting that I was seen by several people running up the trail toward Wineglass Bay and its beach. Later that day there was a rumor at the coffee break that some member or members of our group had been swimming nude in Wineglass Bay. Now I have done a fair share of swimming in the nude, and I did not bring my Speedo swimming suit along on this trip. So it is possible that I was the nude swimmer or was among them, but I was not, to my great regret, swimming naked in Wineglass Bay that day. My life – and perhaps yours – is full of such missed opportunities. Anyway thanks for a great meeting and the sighting of at least one Tasmanian Devil.

You came to visit me in Michigan in 2007 or 2008 and stayed with Mary Ann and me at our home in Grosse Pointe, one of the most pleasant, most safe, most orderly places on earth (that being stated by someone who has lived in 8 states and 2 foreign countries in the last 60 years). On our way to and from my office and lab at Henry Ford Hospital, we toured the depressed, dysfunctional city of Detroit, which lies mostly south and west of Grosse Pointe. The contrast between the abandoned homes and factories of Detroit and the pleasant life in Grosse Pointe was duly appreciated by you and distracted you from my failure to brew our morning coffee with the French press.

So, Norman, we have been the best of friends for many years. I hope that all goes well with your research and your life in Australia. I trust that your hip surgery and arterial stents will permit you to keep going for many more years. Keep up the sailing and stop by for a swim in my backyard pool whenever you can! May the Research Council drop a million Australian dollars on your proposed study of the ABC transporters in the developing brain.

With great respect and love,

Joe

From Helen Stolp

Dear Norman,

I would very much like to add my voice to those celebrating your contribution to science. You have been an amazing mentor and a fantastic support over many years and places. I learnt much from you during my PhD (as would be expected!), and have continued to do so every time we meet at a conference, a lab visit or for a beautiful lunch and gossip in Hobart. You have been a stalwart influence on myself and our scientific network; reminding us of the standards required to make scientific progress, and of what hard work, dedication and passion can achieve.

Congratulations on your achievements and the very best of wishes,

Helen

From Hannelore & Hans

Lieber Norman,

Bleib gesund, lebensfroh und bewahre dir deinen kritischen Geist! Ad multos annos et publicationes!

Hannelore & Hans.

From Geoff Burnstock

Norman has been a good friend for many years. When I arrived from Australia to take up my appointment as Head of the Department of Anatomy and Embryology at University College in 1975, Norman was particularly friendly and welcoming and he gave me valuable insights about people and what to expect in my new challenge. Our friendship continued when he moved first to Southampton, then to Hobart and finally to Melbourne. Since we have been spending a couple of months every year in Melbourne, it has been a pleasure to spend time with Norman, and his delightful wife, collaborating on projects in pharmacology as well as enjoying lunches and dinners together. My wife and I plan to return permanently to Melbourne in November 2017, so we look forward to continuing our friendship in an even fuller way. We wish him much joy on his birthday and in the future.

From Shane Liddelow

Lacking the opportunity to annoy Norman on a daily basis since I left his lab as a bright-eyed and bushy-tailed postdoc, I’ll take this opportunity to comment on not only his commitment to the blood-brain barrier field, but also his commitment to keeping all his trainees honest, eager, and above all else, away from Evan’s Blue! Norman (obviously along with Kate – the unbeatable duo) was my mentor during graduate school in Australia. Of course, we have often argued about when I actually started my time in the lab, as I one day arrived on his door step as an undergraduate stating that I was going to do some research in his lab. As a 20-something year old student, I almost had no idea what I was getting myself into. And as a tenured professor, I’m sure Norman didn’t either – at the time I thought I spent so much time travelling overseas so I could have exposure to the greater scientific communities of Europe and the US, but I often wonder if it was just so he could be rid of me for a few months!

To be fair though, I doubt I would have made it through the maze that is academic politics, or a life as a junior research scientist if Norman had not been available as my scientific guide. This older, gentle, English human anger pot urged me to set aside my ideas of grandeur and world domination and settle in to just ‘do good science’. Norman taught me many things. He introduced me to the complexities of the collective barriers of the brain, and of the difficulties of working in the developing nervous system. He always urged me to probe the science behind the publication – teaching me the all-important ‘question everything’ concept. I fondly remember one time during my Honors Thesis year I was tasked with presenting a paper to my class that was important in my field. As each student stood, presented, discussed, and returned to their seats, I grew ever worried. Such amazing works, such beautiful science, such important contributions for these students to build on. Finally, it was my turn. Carefully trained by Norman, I presented a landmark paper on the early stages of the blood-brain barrier, published in a top journal. I presented the first figure, and then listed all the reasons the figure presented not facts, but instead artifacts. I then proceeded to point out why this paper had slowed down progress in the field for decades. I can still picture the dents left in the lecture room floor by the jaws of my examiners. I knew I had found the right mentor in Norman.

Never afraid to speak out for what he knew to be right, I relished in the (as I realize now) protection afforded by working with Norman to do the same. I always listened, I often heeded, but I’m sure he’ll agree I was sometimes slow to act or too eager to act to be effective. However, I think I have come through it all a better scientist, and I am sure there are countless others who have enjoyed and appreciated his mentorship the world over.

Together with Kate, and a number of long-standing national and international collaborators Norman has continued to be a dominant force in not only the field of brain barriers, but also spinal cord injury. Always applying new techniques to answer important questions, returning to old techniques when they are the most appropriate (my own students still find mouth pipetting of CSF samples an outrageous idea!). In a world with what appears ever decreasing funding and respect for science, education and support like Norman has always provided the way forward to ensure the next generation of scientists can be held in the highest esteem. Norman will always be a key pillar in his fields, and I am sure he will continue to inspire others as he has inspired me into the exciting life of academic science. I am deeply grateful for his contributions and support, and I promise to never use Evan’s Blue in my own lab.

From Ben Wheaton

Probably like a lot of people here, I did my PhD in Norman’s lab. His advice when I started was simple: “If you make a mistake, tell someone. We don’t want to spend years chasing a result that was done in error.” This piece of advice, delivered on my first day, has stuck with me for longest time and I think has helped make me a much more careful scientist than I otherwise might have been.

I’m sure I’m not the first to point out the incredible breadth of Norman’s work involving axon transport, development, barriers and spinal injury—even sailing. Norman has been not just a significant figure in neuroscience but also a significant figure in the scientific lives of all who have worked with him.

Among the many important perspectives Norman has been able to bring is the instilling of a healthy dose of skepticism in all things scientific, the ability to impart important lessons on a staggering array of topics, and a constant imploring to consider what is really important.

His incredible work ethic, persistence and willingness to throw himself into new fields and challenges should serve as an inspiration to us all. It has been truly an honour to learn from someone with such a deep and expansive perspective on a great many things. You couldn’t ask for a more supportive supervisor. Thank you.